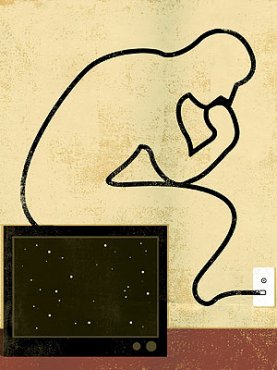

Cable TV and broadcast TV purvey different worlds, and cableÂs… (Edel Rodriguez / For the…)

Cable TV and broadcast TV purvey different worlds, and cableÂs… (Edel Rodriguez / For the…)

Back in May 2001, then- NBC President Robert Wright was fuming. He fired off a bristling letter to producers and executives throughout broadcast television, complaining that HBO was changing the rules of their medium. Wright's immediate gripe was an episode of "The Sopranos" where a young stripper was beaten to death by a berserk Mafioso. But his larger claim was that broadcast television was having a hard time competing with the cable network because it had the license of unexpurgated language, nudity and bloody violence that were proscribed to NBC. If only his network had the freedom of HBO, well . . .

Wright might have honestly believed that the difference between NBC and HBO was a matter of cussing and graphic violence, but he could not have been more wrong, then or now. The real difference between broadcast television and cable is not that the Federal Communications Commission restricts one from doing what the other can. It's a matter of cosmology - the way they perceive the universe. Cable TV and broadcast TV purvey different worlds, and cable's is darker, bleaker, more complicated and less forgiving.

This shouldn't be too surprising. Broadcast television was devised in the late 1940s to reach the broadest possible audience in order to sell sponsors' products. Because it would eventually enter nearly every living room in America, it was compelled both by government regulation and its own sense of decorum to behave like a proper guest. From its earliest variety shows, which were direct descendants of vaudeville and shared vaudeville's family appeal, to its earliest sitcoms, which were descendants of radio and shared radio's disinclination to offend, to its earliest dramas, which descended from the movies and made a similar appeal to the middle, television felt safe.

Broadcast TV operated within a world vision that was also comforting. Television shows invariably had closure. The basic principle of broadcast TV, whether a program was comic or dramatic, was that a situation would arise in one act only to be resolved in the next. Nowadays, there are longer story arcs - " Lost's" has lasted six seasons - but the same idea obtains. Nothing is open-ended on broadcast television. Nothing is intractable. It is a form without anxiety - a form of reassurance.

What is true of broadcast TV's narrative technique is also true of its protagonists. The likable hero - "The Mentalist, " the investigators on "NCIS, " the detectives and lawyers on the various "Law & Orders" - is so much a commonplace that it is easy to overlook just how much he or she constitutes a complete attitude, especially since the source of his or her likability, aside from appearance, is typically his or her basic decency. Broadcast TV trades in a good world filled with good people - a world in which evil is an aberration and not a condition of life. Think of " Criminal Minds, " in which a team of profilers tracks down a vicious serial killer each week without the whole world ever seeming awry.

The heroes may be conflicted or idiosyncratic or errant, but we never doubt their fundamental morality, just as we never really believe in their complexity. On broadcast TV, cops exist to fight evil, doctors to save lives, Moms and Dads to love their families, and twenty- and thirtysomethings to love their friends.

Cable television purveys a very different world view - at least in many of its precincts.

On the USA network ("Characters Welcome"), characters are likely to be either eccentrics - to wit, the obsessive-compulsive detective Monk - or individuals who have suffered a setback - a CIA agent who is suddenly dropped on "Burn Notice, " a young doctor whose practice goes belly up on "Royal Pains" - and then must adjust. They don't make the world right. They try to make the best of things.

It gets a tad more interesting with TNT ("We Know Drama"), though the network's characters and their world are not radical departures from broadcast TV either, just less overtly good in a world slightly less redeemable at show's end. What is different from NBC, CBS, ABC or Fox on shows such as "Dark Blue" or "The Closer" or "Southland, " which was pitched overboard by NBC precisely because it didn't seem like a crowd pleaser, is the darkness of hue, the whack-a-mole persistence of the bad that begins to bring into question whether evil is limited to the social margins.

AMC goes further. Don Draper, the creative adman extraordinaire on " Mad Men, " isn't just not overtly good; he is so deeply flawed that both his likability and his possible redemption are seriously in question. A serial philanderer, a bottom-line boss who fires a gay employee for not succumbing to the advances of a client, a man whose entire life, including his name, is a lie, Draper is a cunning man in a mendacious, predatory world of images. There are no happy endings here, only triumphs of guile and will.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE